Orc painting!

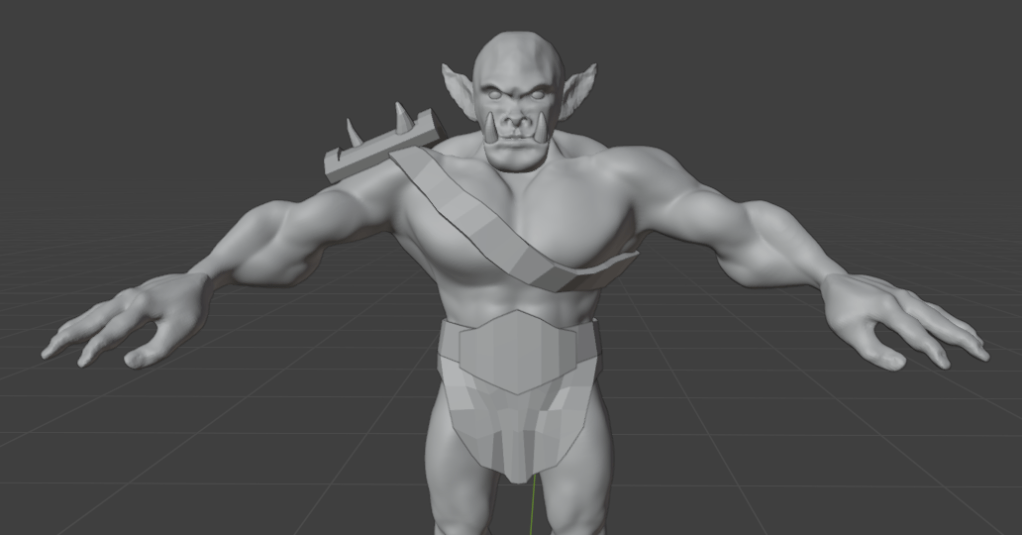

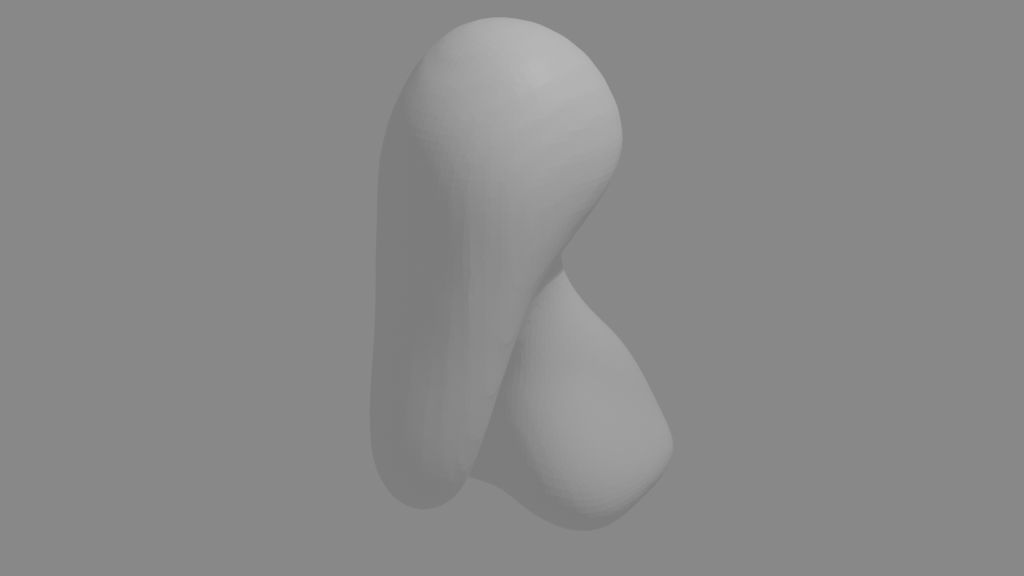

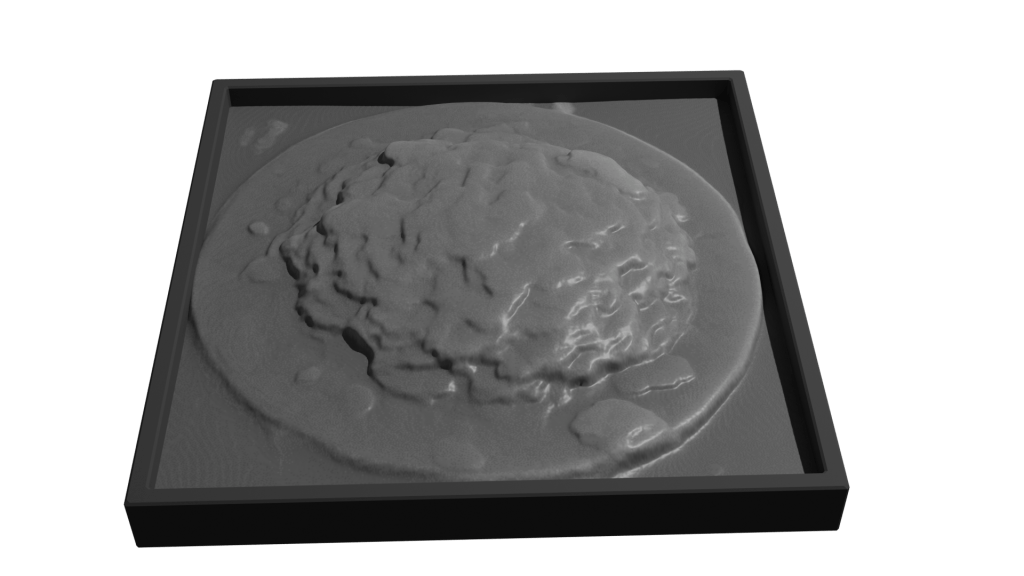

Last time, I had made a nice looking orc1.

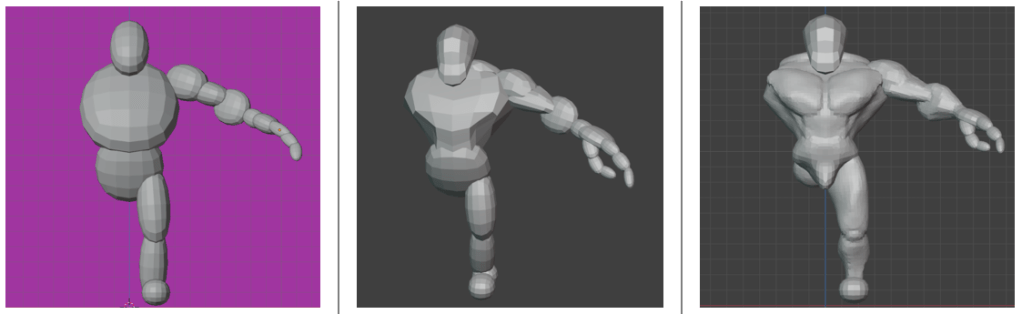

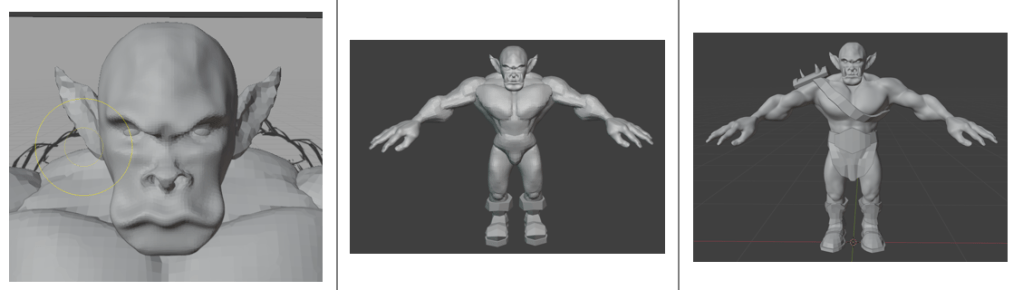

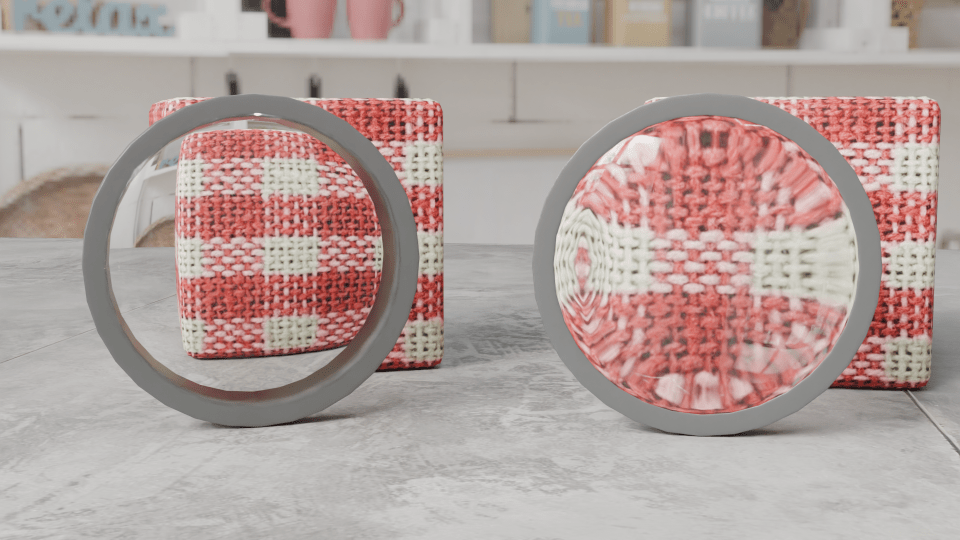

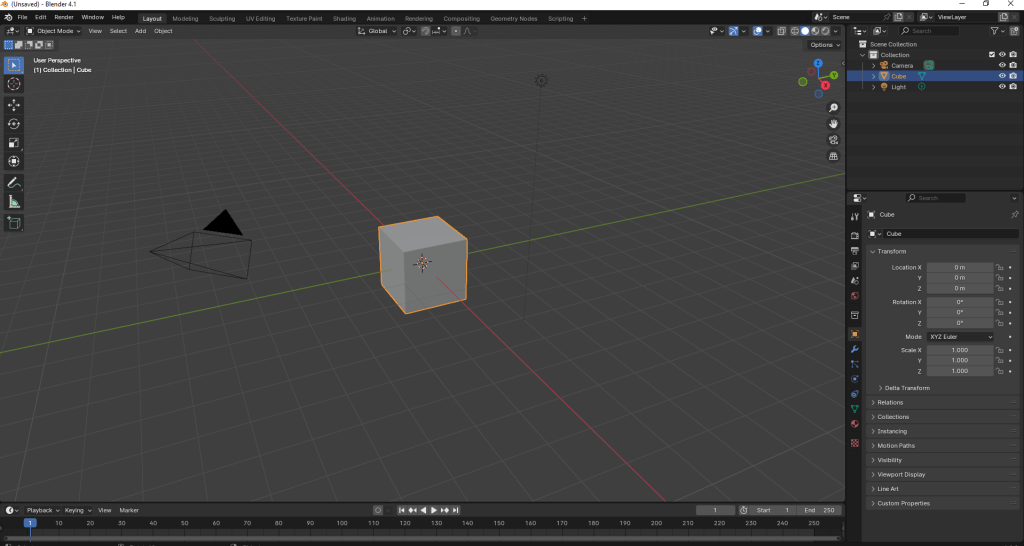

The next stage was quite complex and not very visual for blogging purposes, except that the end result was obviously an image. It involved baking textures and it’s why we spent time on getting the musculature and the facial features right. It’s all to do with poly count.

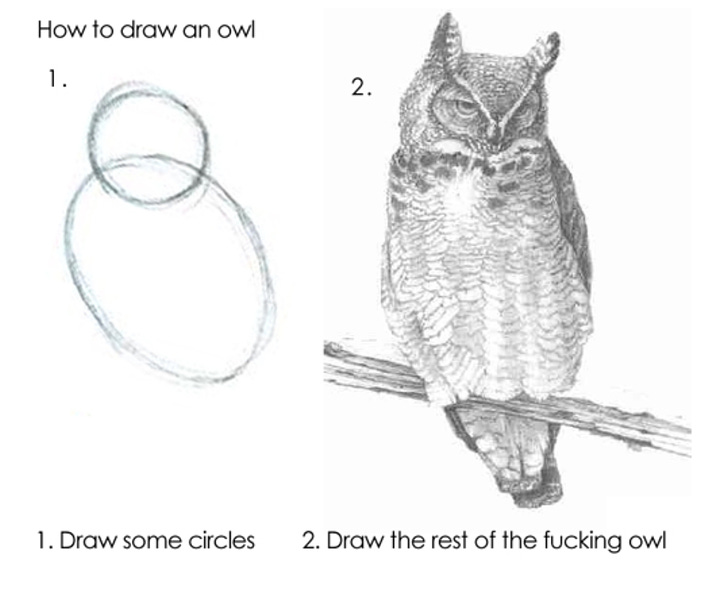

The number of faces (polygons) in a model is an important factor in 3D modelling. The more faces you have, the better your model will look. The drawback is that these polygons take some time for the computer to calculate. This slows down your work and can result in the computer crashing.

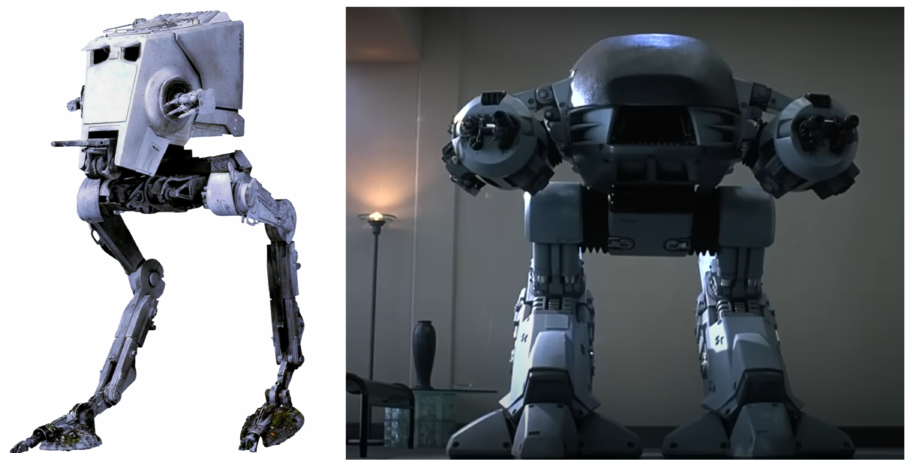

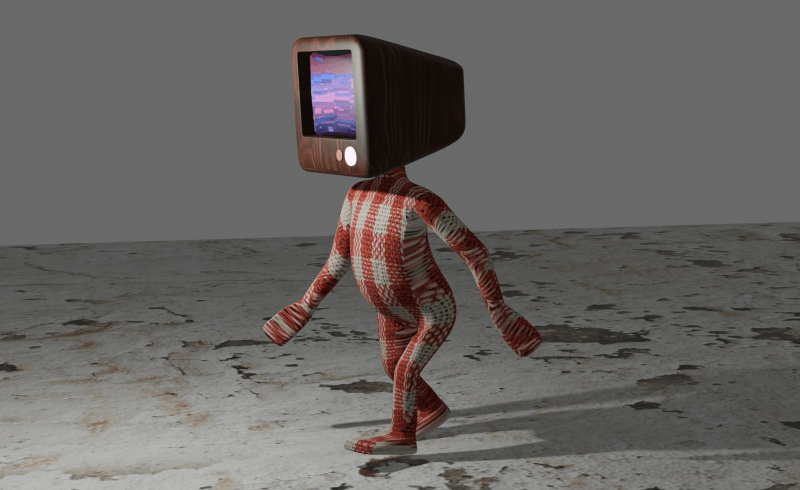

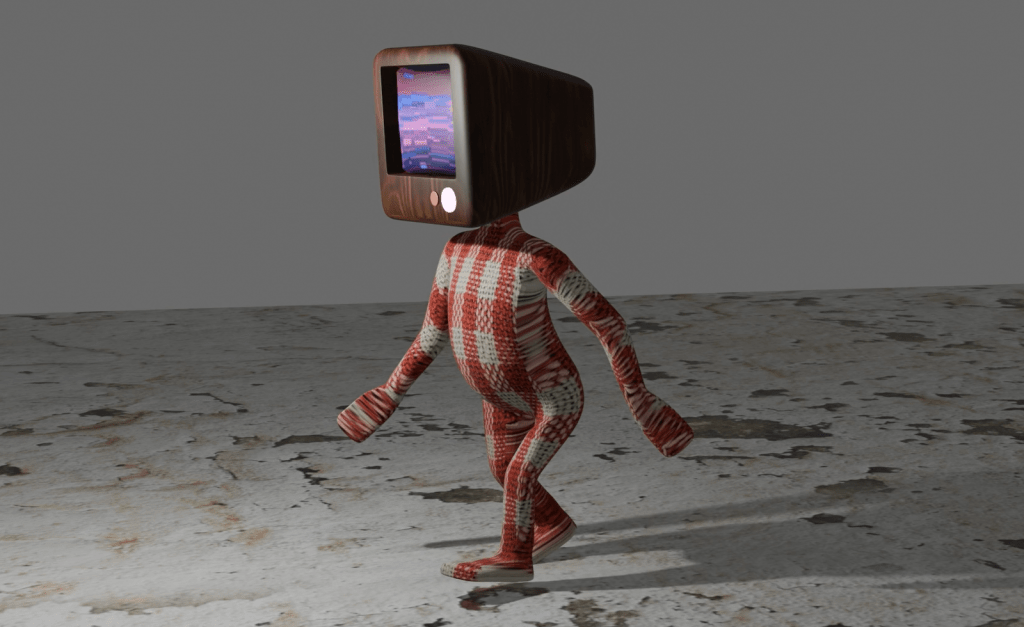

By way of illustrating this, the face count for the model shown at the end of the last section and below was 14.5 million and a file size of 160 MB. By baking the textures onto a lower poly duplicate of the original, this comes down to 47,000 faces and a 64 MB file.

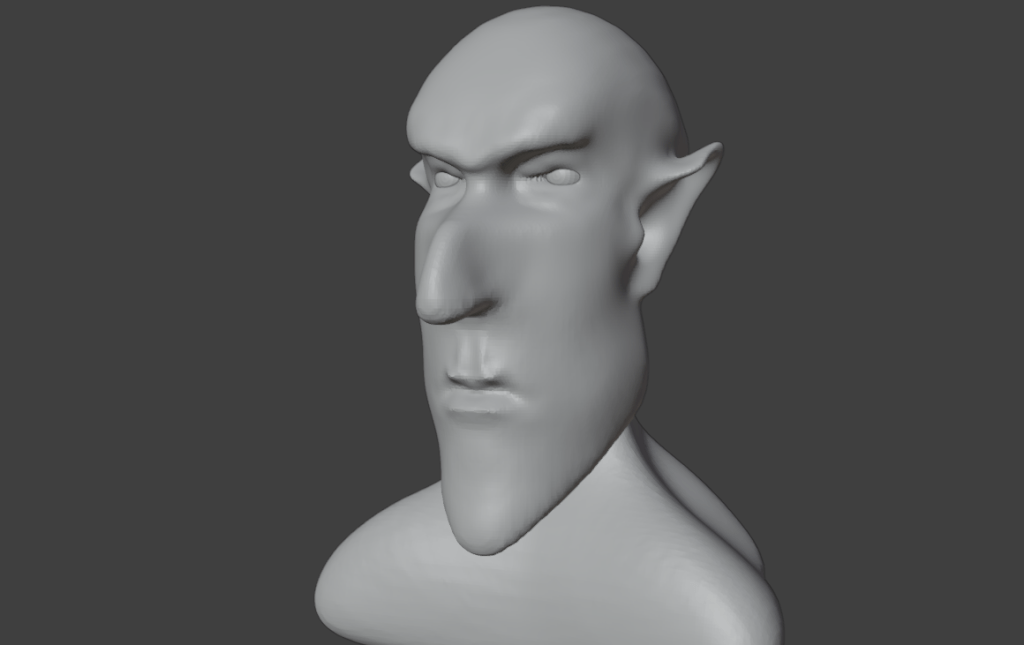

Baking is the process where details from a highly detailed model, such as shadows from clothes and weird veins and scars, get painted onto a lower poly mesh. The details aren’t there, but look like they are.

Baking textures allows you to use a low poly mesh that looks like a high poly mesh. The disadvantage is that you can’t change you mind about, for example, the position of the clothes once the bake is done. You can always repeat the bake, which takes a bit of time and isn’t very exciting.

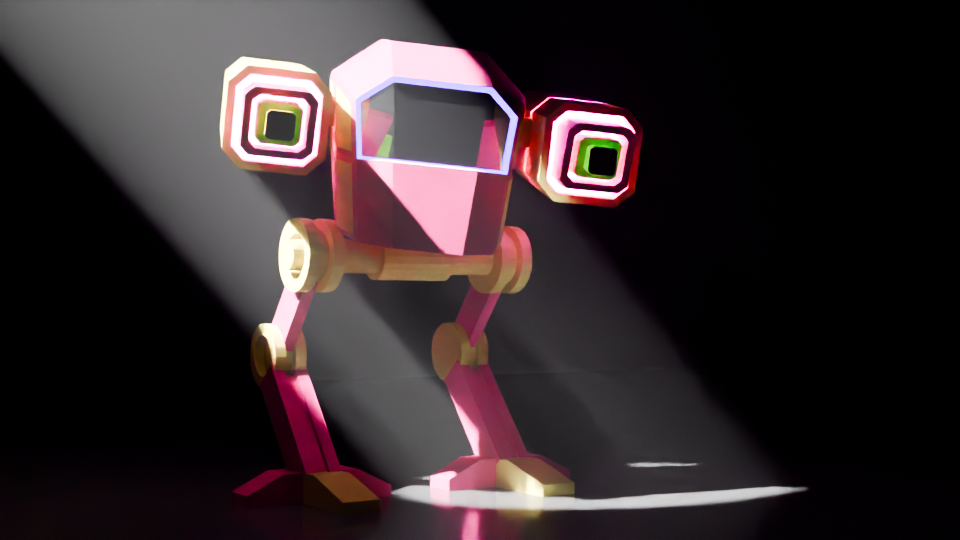

In the end, I’m happy with how Steve turned out. There are a few mistakes with the painting, but if you can see them keep it to yourself. I should go back and re-do where I went wrong as an exercise.

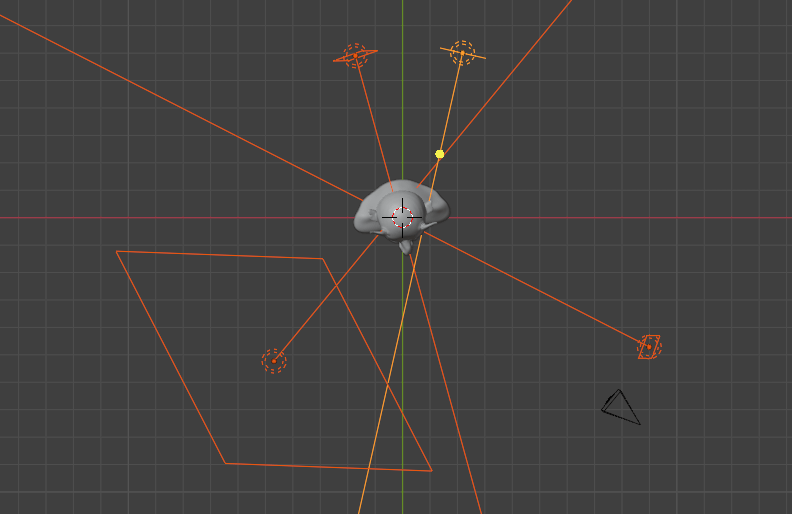

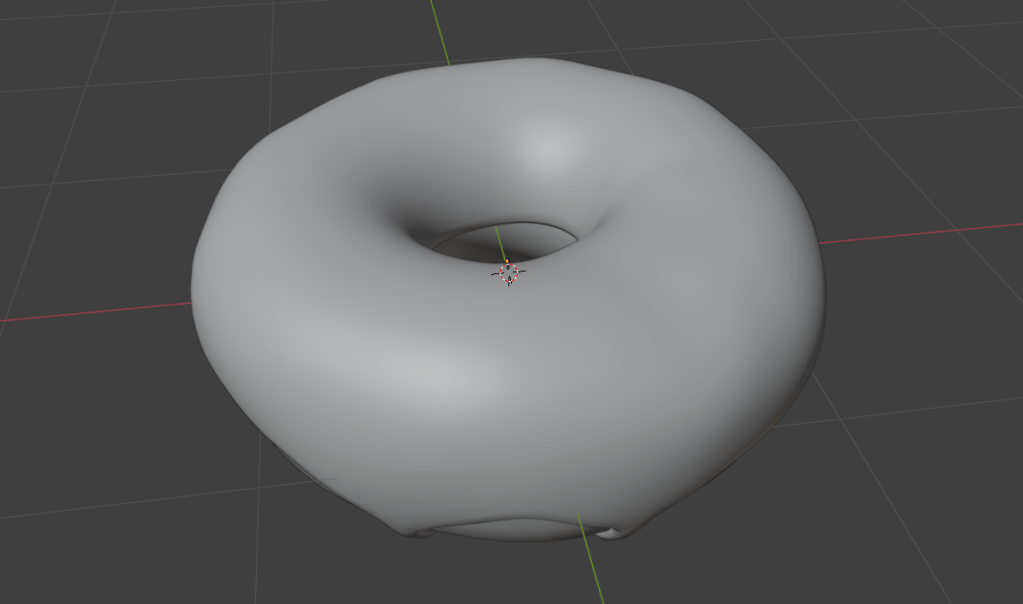

So I had an orc with bones that I could manipulate and pose in a threatening manner. But the hands were wrong – the fingers looked awful when I tried to make them grab anything. That was the next thing, because I wanted to make Steve grab things and make a fist. That was for another time, though.

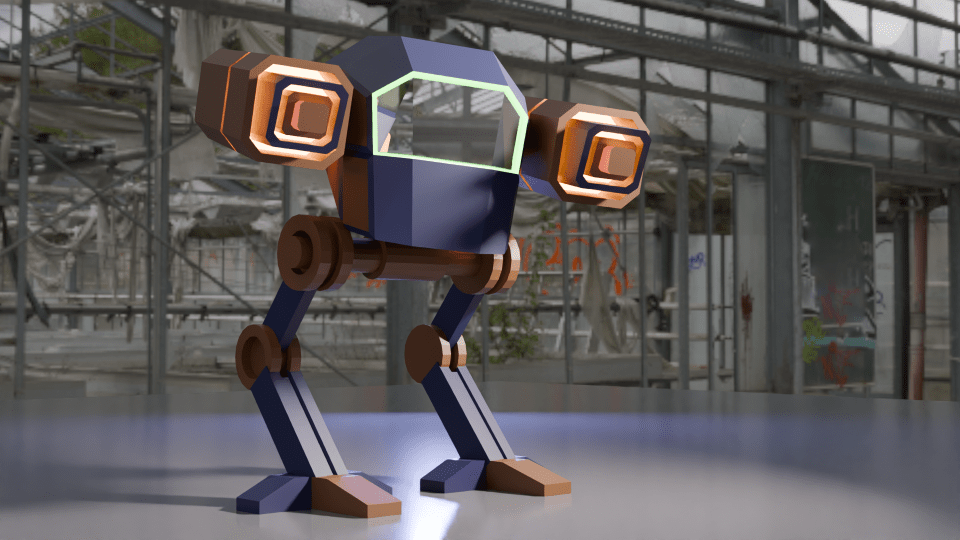

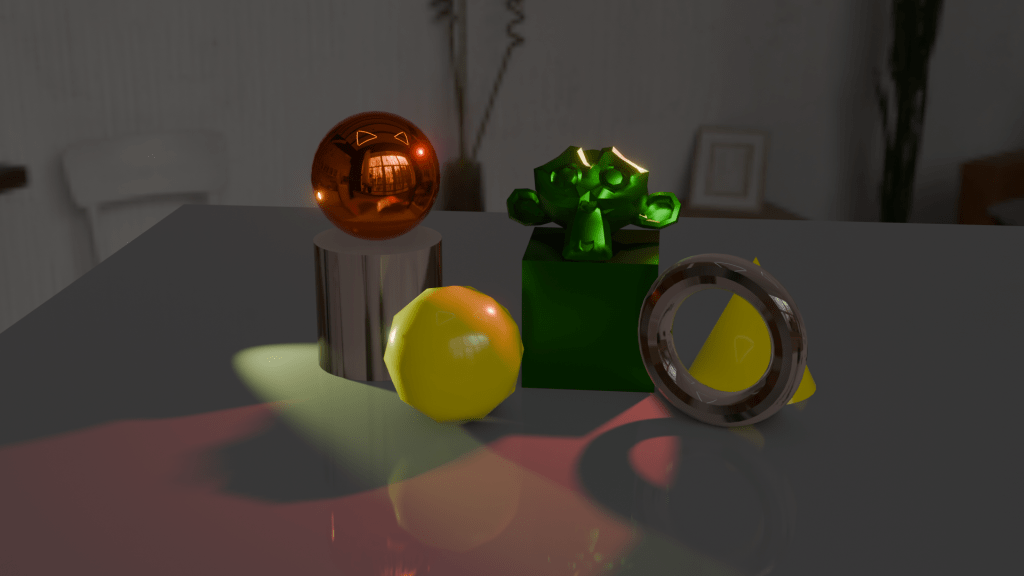

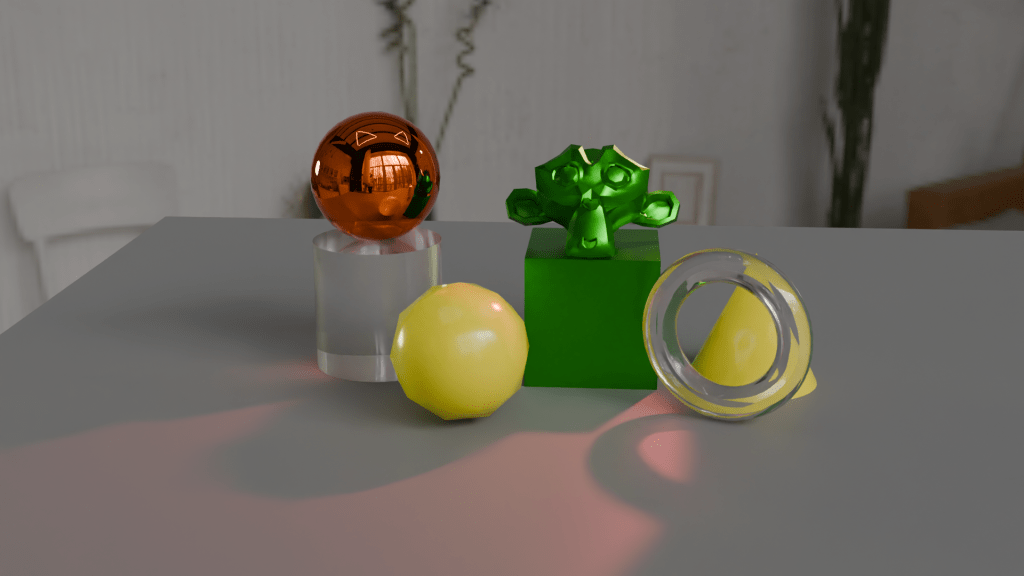

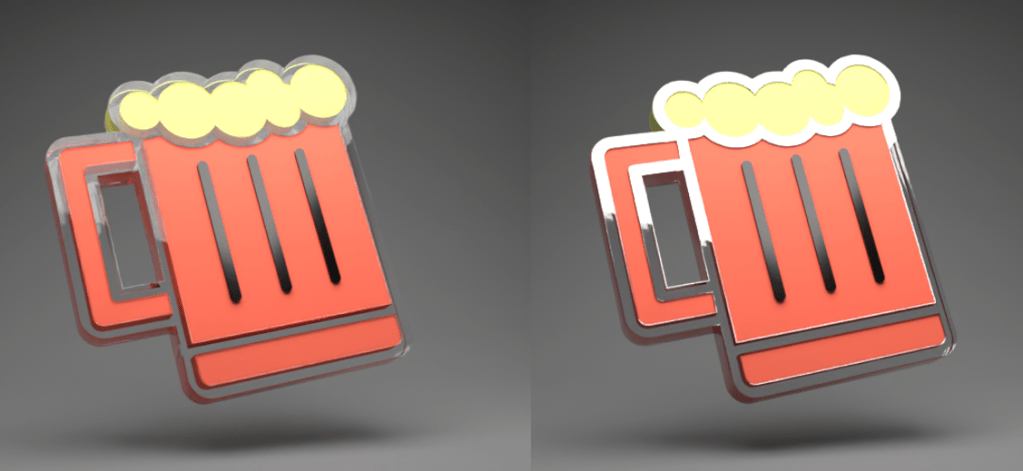

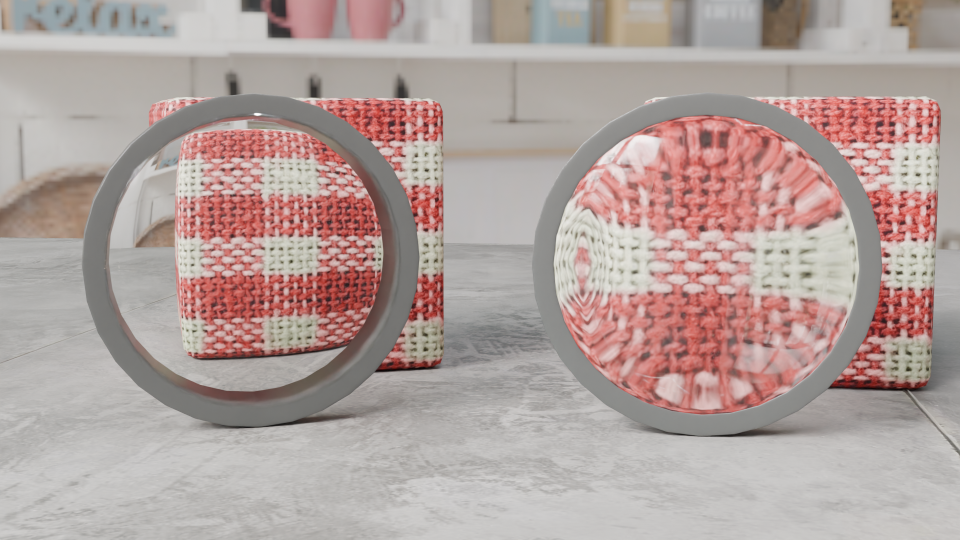

So that was the course finished. Next up, I’ll have a look at getting realistic textures onto objects and then I’ll try and get those hands looking right so I can pose and animate Steve. And don’t forget to look for science-related opportunities for Blender.

- You know what I mean. ↩︎