Saturn’s sixth-largest moon may have the right conditions for life. But how to prove if there is life on Encaladus?

Background – Cassini-Huygens mission

The Cassini-Huygens mission was launched in 1997 with the mission objective to explore the saturnian system. It would take seven years to reach Saturn, and it would collect images, chemical analyses and magnetic field readings as it passed through the inner solar system, the asteroid belt and past Jupiter.

This would be the first mission to orbit Saturn and would carry the Huygens lander, which landed on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Among the instruments on the Cassini probe there was a mass spectrometer, the Cosmic Dust Analyzer1, which was designed to collect and characterise cosmic dust.

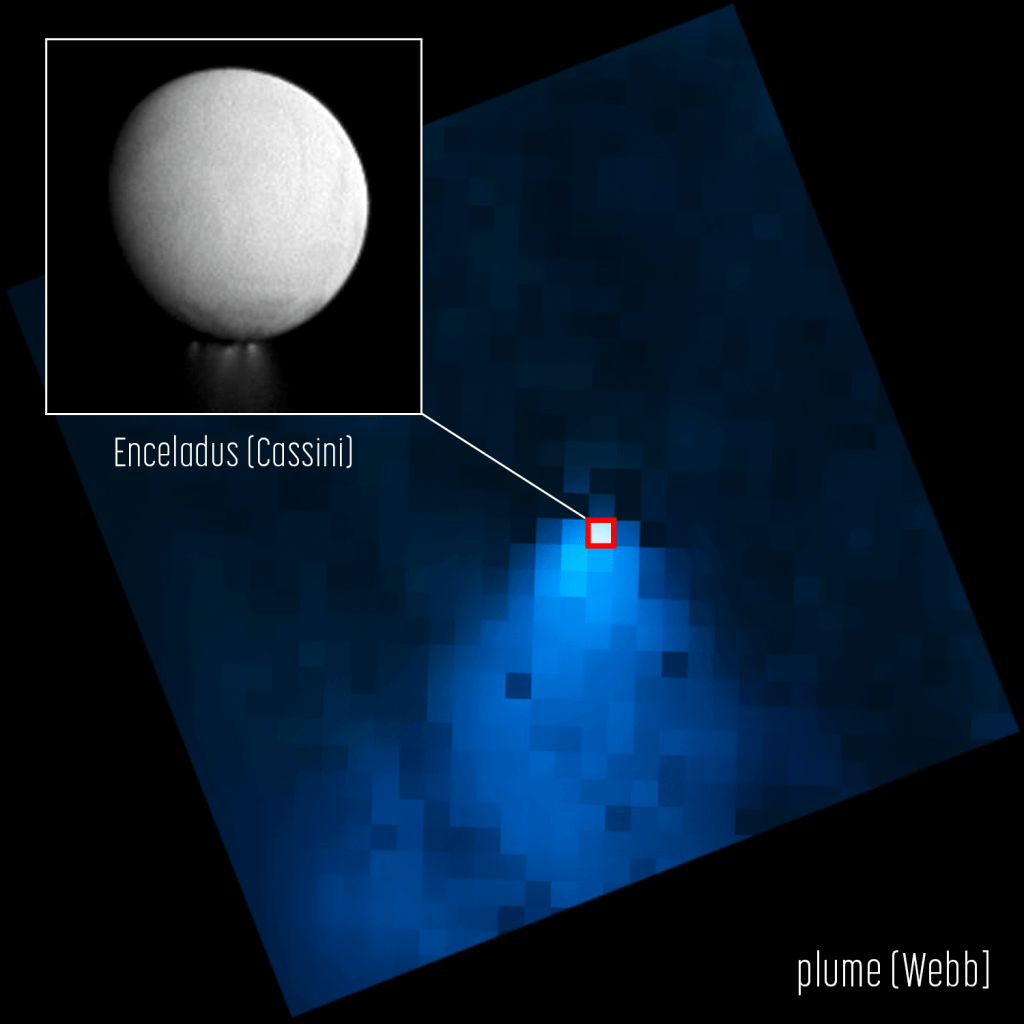

Among the many amazing discoveries on the mission was the observation of gas plumes – cryovolcanoes – erupting from the southern polar region of Enceladus, the sixth-largest of Saturn’s 274 moons2 .

Further observation and analysis of the plumes showed that they were mostly water and these ice crystals also constituted much of Saturn’s E-ring, the fifth ring to be discovered, whose existence was not confirmed until 1980.

Astronomers reached this conclusion from the chemical analysis provided by the CDA in the early part of the mission. Collecting dust from the E-ring and from around Enceladus, it was seen that the chemical make-up of the ice crystals in the ring and in the plumes matched. However, looking again at the chemicals trapped inside it was concluded that the water coming out of Enceladus was salty and contained not only silicates, but ammonia and organic chemicals of varying complexity.

A recent publication in Nature Astronomy3 has summarised the analysis of data collected by the Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA) during the last part of the probe’s orbit of Saturn from 2004 to 2017. The organic chemistry observed in these analyses shed light on the make-up of the oceans of Enceladus and raised the possibility that the moon is capable of supporting life.

The first question that needs to be asked in the search for extra-terrestrial life is whether the conditions are suitable for life to exist. Liquid water at a reasonable temperature and pH is one such condition4. Also, six elements – carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulphur – are regarded as necessary for biological systems to survive.

Enceladus

Enceladus was discovered by William Herschel in 1789. Not much was known about it before the Cassini mission. It was known that it was 500 km in diameter – one seventh the size of our moon – and was associated with Saturn’s E-ring, though how the two interacted was not known.

Analysis of the magnetic data that Cassini collected provided astronomers with a update on the structure of the moon. There is a rocky core and an icy upper crust – this much was known. But data strongly suggested that there is a liquid ocean between the rock and the ice. This is a salty, high pH (11 to 12) environment but crucially there is liquid water.

The article by Khawaja et al provides an analysis of some of the data the CDA collected in the last months of the mission. It has taken years to refine the data to the point where statistically significant conclusions can be drawn. A lot of the information from the Cassini fly-past was collected at relatively slow speeds. And ‘relatively’ means less than 12 km/s. Data from higher speed fly-bys at up to 18 km/s were also collected and form the basis of the new analysis.

The speed at which the crystals were collected matters. The way the CDA works is that the crystals would hit a screen at the front of the CDA. The crystals are tiny – at most 1 nanometre (one millionth of a micrometre) and some ten orders of magnitude smaller (10-19 m)5. In the time it takes the ionised particles to reach the detector (about 20 microseconds at lower speeds) the water will freeze and this can shield many of the analytes from the instrument. At higher impact speeds the ice did not have time to reform and so more of the trapped chemicals were visible to the detector.

With faster incoming particles, the detector had to work faster to be able to distinguish between each particle. Higher speed detection required the analyser to work at its maximum rate and in a mode for which it was not really designed. The data were noisy and in the years since a great deal of effort has been spent finding enough useful data to be able to make conclusions.

What was found was some volatile organics such as methane and ethane, plus a mix of volatile low-mass nitrogen and oxygen bearing organics, single-ring aromatics and some complex macromolecular species, up to the limit of detection of the CDA (about 200 Da).

This complex mix of chemicals can be seen as the building blocks for life and raises the question of what the source of these chemicals could be.

In all this, you have to bear in mind that the CDA was designed and built nearly 30 years ago. Computer speeds have increased massively since the mid 90s and a CDA designed now would be smaller and more efficient than the one on Cassini. But also a CDA built in 2055 would be more advanced again.

James Webb

The James Webb telescope, launched in 2021, has investigated Enceladus. Using near infrared – more sensitive to water than the instruments on Cassini – it detected water plumes extending 10 000 km from the moon. Enceladus itself is only 500 km in diameter.

New missions to Enceladus have been proposed, but are not likely to take place any time in the next ten years. The tantalising possibility that there is life on another body of the solar system has taken a step closer with these data.

The mix of chemicals determined to be in the plumes, and therefore in the oceans of Enceladus, are known to be those that support life. Until or unless we get a sample of an enceladan microbe under a microscope there won’t be proof of life there. The data reported by Khawaja doesn’t mean that there is definitely life on Enceladus. It does mean that it’s possible.

- Full description in Srama et al (2004) Space Science Reviews 114: 465-518 ↩︎

- At the time of writing, there were 274 named moons. More may well be found in the coming years. ↩︎

- Khawaja et al (2025) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02655-y ↩︎

- The limits of ‘reasonable’ has changed over the last few decades. Extremophile microbes capable of surviving and thriving at temperatures of 120 °C and pH up to 11 have been found. ↩︎

- This is a huge dynamic range for the detector to be able to analyse. It’s like being able to analyse a grain of sand and something the size of the Earth’s orbit in the same instrument. ↩︎

Leave a comment