“We are about to jump into hyperspace for the journey to Barnard’s Star. On arrival we will stay in dock for a seventy-two-hour refit, and no one’s to leave the ship during that time. I repeat, all planet leave is cancelled. I’ve just had an unhappy love affair, so I don’t see why anybody else should have a good time.”

Cpt Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz, Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Over the last 20 years, thousands of exoplanets have been discovered (5867 in 4377 systems according to Wikipedia). The first confirmed exoplanet was announced in 1992, when planets were detected around a pulsar.

Pulsars are rotating neutron stars that emit a highly regular beam of electromagnetic radiation1. The pulses emitted by a pulsar with a planet are slightly altered by the presence of a gravitational field, such as that caused by the presence of a planet. It was anomalies in the pulse period of a pulsar in the constellation Virgo that led to the discovery of the first exoplanet. Or rather exoplanets, because this pulsar has three, including one that is half the mass of the Moon.

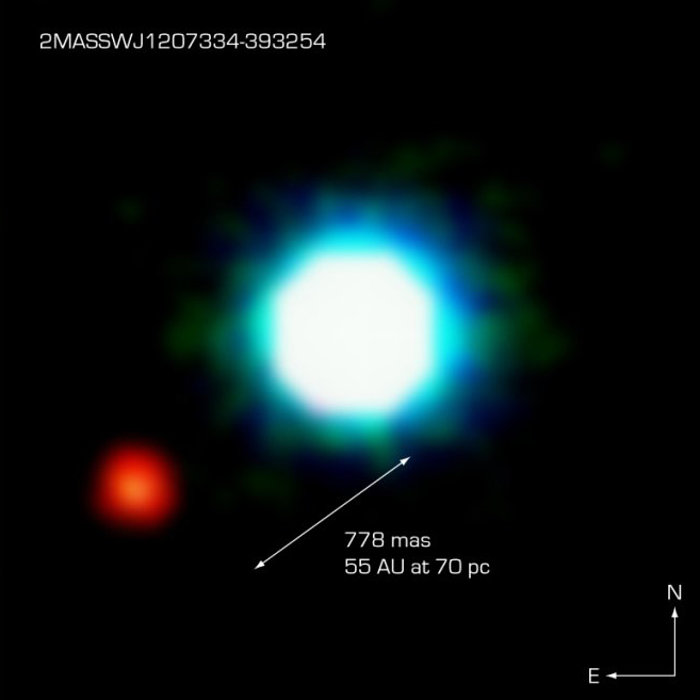

Direct imaging wasn’t really an option until much later. The first exoplanet to be directly imaged wasn’t announced until 2004, when 2M1207b was observed orbiting its parent star the brown dwarf 2M1207 (in the constellation Centaurus), 170 light years away by the Very Large Telescope in Chile.

To date (4th April 2025), 128 stars have had planets directly observed around them, (including one with four planets). Our closest star, Proxima Centauri, was shown to have a planetary system in 2016; a third planet was announced in 2022.

The Hubble telescope and, more recently, James Webb telescope have provided direct images of many more exoplanets. Spectroscopic analyses have given us insight into the atmospheres of some of the planets.

Barnard’s Star

Anyway, back to Barnard’s Star. This is one of the closest stars to Earth, though it is so faint that it wasn’t discovered until 1916, by Edward Barnard. He announced the discovery of a star with a large proper motion (how far it appears to travel) after observations 14 days apart. He followed this up with reference to observations made in 1894 (Lick Observatory in California) and 1904 (Bruce Observatory, Whitby), where the star showed up on earlier photographic plates. From this, he calculated a proper motion of 10.3″ a year, or one degree every 6 years.

So it’s moving fast. And it’s getting closer. It’s one of the few objects in the sky with a blue shift — the most important other one is the Andromeda Galaxy, which is approaching the Milky Way at about 110 km/s; they are expected to collide in 4 to 5 billion years. Get your crash helmets ready.

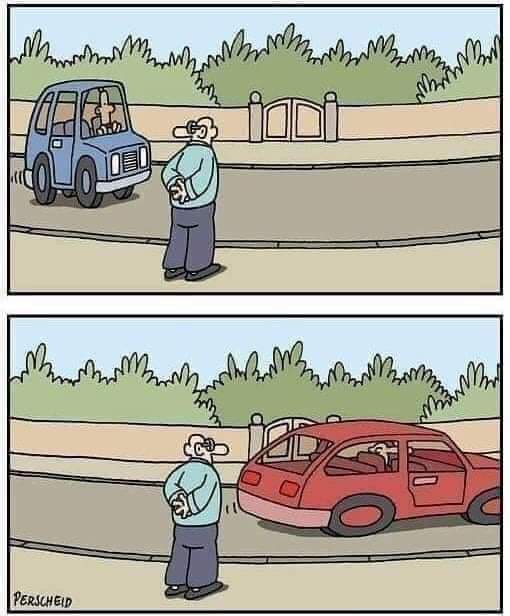

Blue shift is the opposite of red shift. Light is ‘shifted’ when the expected spectrum of light from the star is different to what is expected from the known emission spectrum of the elements in the star. It’s also known as the Doppler Effect and is the basis of this cartoon by the German cartoonist Martin Perscheid.

So we have a star that’s approaching and it has at least four planets. Why the fuss? Well, there have been plans to visit either Barnard’s star or the Alpha Centauri system. Back in the late 1970s the idea was mooted to build a probe capable of travelling one-tenth the speed of light. The probe would take forty years to get there, and another four years before any signals from the probe arrived at Earth.

So we could now be getting images of planets from a probe that was launched before we even knew that these planets existed.

- There’s some physics behind this that I don’t fully understand. ↩︎

Leave a comment