I don’t think of myself as a whisky aficionado or expert in any way. As far as I’m concerned, I know what sort of whisky I like but I don’t think I have sensitive enough taste buds to distinguish and separate different flavours within a drink. The divide in whisky for me is between peated and unpeated. I find that peat in whisky overwhelms any other flavour; I know others disagree (having had a few discussions on this topic at work) but if we all liked the same thing then it would always be sold out.

But where does the flavour of peat in whisky come from?

Why write this article if you don’t like peaty whisky?

Good question. This article was stimulated by an email I got from Wolfburn Distillery1. They were advertising new, peated expressions of their whiskies. Not much to interest me there; as I said I’m not a fan of peaty whiskies. I prefer the floral and fruity whiskies of Speyside and I’m also partial to Old Pulteney’s (Wick, Caithness) slightly salty ‘Maritime Malt’ output. What triggered my interest and sent me down a rabbithole was that they included a ‘ppm’ in the description of the peatiness.

With a career in science, I knew that ppm means ‘parts per million’ and is a unit of concentration. But concentration of what? A quick Google revealed that this is the level of cresols in the barley. Since ‘cresols’ covers a wide range of chemicals and there aren’t normally cresols in barley, the further questions were – what cresols are there in the barley, and how do they get there?

Peat and whisky

To answer the questions we need to understand how and where whisky is produced. The ‘how’ is not a mystery, though there is a lot of chemistry and craftsmanship involved. You start with barley and several years later, you have whisky. The ‘where’ is Scotland for the purposes of this article. But where in Scotland?

For the purposes of answering the question of ‘how do cresols get into the barley?’, the processes of malting and kilning are the important parts. Malting involves soaking the barley for three days to start germination and trigger the enzymatic conversion of starches into sugars for later fermentation. Kilning heats the barley, stops the germination and dries the grain before the milling stage. It’s the kilning that introduces the cresols.

The fuel used in the kilning is where the peatiness is added. Traditionally2, if you’re producing whisky in the Lowlands or your distillery is near a railway line, then the fuel of choice would be coal. It’s cheap, efficient and doesn’t alter the flavour of your product. If you’re producing whisky on an island off the coast of Scotland, you don’t have coal. What you do have is peat, and this is a useful resource for heating homes and kilning your barley. This, then, is the reason why island whiskies such as Laphroaig (Islay, Inner Hebrides), Torabhaig (Skye) and Highland Park (Orkney) tend to have a characteristic peatiness.

The cresols from the peat adsorb onto the barley, and the grain acts as a vehicle to carry these alcohol-soluble chemicals into the next stage and ensure they remain until the drink is drunk.

Cresols

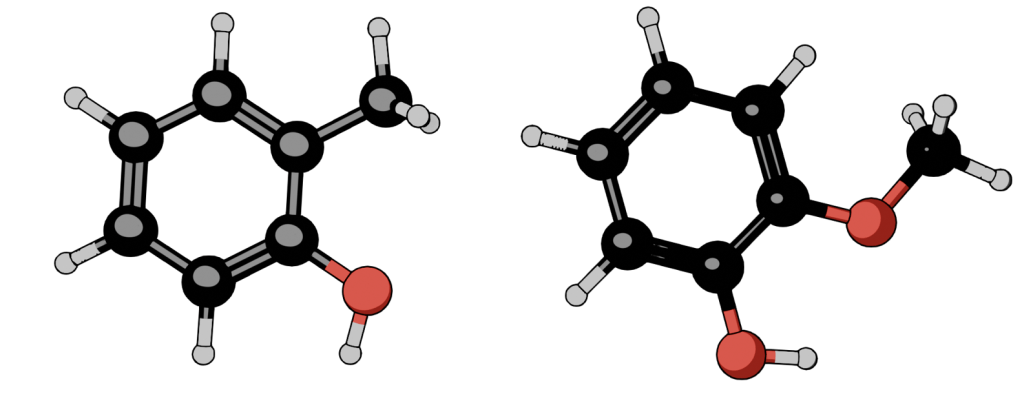

Cresols as a group are based around phenol (hydroxy benzene). Chemically, they are all classed as ‘aromatic’, a name that was applied to a range of chemicals that were strong smelling, often coloured, had some unique chemistry and were sometimes carcinogenic.

The main cresols in peated whisky are guaiacol and the ortho-, meta- and paracresols. The tarry and smoky characteristics are given by these molecules. Other cresols add different flavours. How such similar molecules can give such different flavours is still not fully understood3.

The cresols found in peats have a range of boiling points which means that they are carried over and separated at different times. Higher molecular weight cresols tends to be distilled off later and these are the strongest tasting chemicals.

The concentration of cresols in the barley is what whisky producers quote. This isn’t necessarily the level in the final whisky, though. As previously said, the cut taken will affect the range and type of cresols in the final whisky. The ‘cut’ of the distillate will capture different cresols, giving the final whisky a variety of flavours derived from the peat.

A good example of how the cut affects the flavour is to compare the Islay whiskies Lagavulin, an exemplar of peaty whiskies, and Caol Ila, a lighter, peppery whisky, used as part of the Johnny Walker Black Label blended whisky. Both start with about 35 ppm phenols (including cresols) in the barley they source from the same maltings in Port Ellen. However, the Caol Ila distillation is an early cut using a reflux still, taking in the lower boiling-point cresols and fewer total cresols. Lagavulin uses a more traditional still and a longer, slower distillation which captures more of the high molecular weight cresols and gives the whisky its celebrated medicinal character.

Other flavours – barrel aging

The spirit that comes out of the still at the end of the distillation process is a sharp, barely palatable liquid with a 70% ethanol content. Pure ethanol isn’t pleasant, as I know from getting some splashed in my face when I was a chemistry student. So this liquid needs to have flavour, and the flavour needs to be developed. This is done by barrel-aging the spirit to get whisky.

Barrel-aging can be envisaged as a very slow extraction process where the alcohol absorbs the chemicals in the wood over three to fifty or more years. As industrial processes go it’s not very speedy, but the end product is fantastic.

History of barrel-aging

In the 15th century, there was a need to store and transport whisky and used wooden barrels were handy. As a side effect it was found that the stored spirit had a more pleasant flavour as the flavours of the wood and the liquid previously stored were absorbed into the whisky.

By the mid-19th century the standard practice was to age whisky in used sherry barrels. Sherry was transported to the British market in barrels and bottled locally to save money on the transport of glass and reduce the risk of breakage. These used barrels could be bought cheaply by the distilleries since the Spanish sherry makers didn’t want them back.

In the 1950s the opportunity to buy used bourbon barrels from the USA meant that there was an alternative to sherry casks. Bourbon barrels can only be used once; by law bourbon must be matured in first-use charred American oak. The flavours of the bourbon and the charring as well as notes from the oak wood itself impart flavours to whisky during the aging.

The availability of bourbon casks was fortunate – in 1986 the supply of sherry casks dried up when the Spanish government decreed that all sherry must be bottled in Spain.

Alternative barrels

Other casks have been used for a different flavour profile: rum, cognac, red wine and white wine. One of my favourites is a port-casked whisky (Tamnavulin Port Cask, a Speyside distillery). This is somewhat ironic, since port and all red wine make me ill; clearly whatever I react to is not present in the barrels to be extracted by the whisky.

Barrel aging means that alcohol is lost to the atmosphere and the local air also imparts its character. The above-mentioned Old Pulteney has a slight saltiness, in part due to the warehouses being situated by the sea. This isn’t a unique occurrence – many of the island distilleries have seaside warehousing. I don’t know why Old Pulteney has this consistent saltiness that other malts lack.

In summary

This was an interesting rabbithole to dive down. I’ve ignored the chemistry of peated whiskies, mainly because my tastes are not for these drinks. But to learn how the flavours are built in to the whisky and also how the barrel storage adds the main characteristic flavours of my own preferred whiskies has been fascinating.

- Wolfburn (Thurso, Caithness, where I was born) isn’t the only distillery to offer peaty expressions. Aerstone (Ayrshire) have a ‘legacy’ expression with peaty notes to complement the ‘sea cask’ that is one of my favourites. It’s similar to the Old Pulteney I mentioned in the Introduction. ↩︎

- Modern distilleries use oil or gas to kiln the malt. ↩︎

- If I do a post on the quantum biological explanation of the sense of smell, I’ll try to remember to link back to this article. ↩︎