An experiment with bourbon may explain the high reputation of Japan’s whiskies

During my research for an earlier chemistry of whisky article, I came across an account of an experiment on how transporting barrels impacts the flavour of bourbon. Bourbon barrels are commonly used to age whisky not only in Scotland, but in England, Ireland, Japan and India.

I’d been looking at how the flavours of charred oak affect the character of bourbon. This article in Wine Enthusiast drew my interest. It described a fascinating experiment by Trey Zoeller, the founder of Jefferson’s bourbon distillery in Kentucky, USA. I originally put it in a footnote, but the whole thing became a bit extended and so I decided to convert it into an article.

Barrel aging bourbon

The usual practice when aging whisky/ whiskey1 is to have the barrels stacked in a warehouse holding maybe 60,000 barrels with 200 litres in each and let nature take its course.

Since 2012 Jefferson’s, based in Kentucky, has offered a limited ‘Ocean Cask’ expression. They send the barrels on six-month voyages at sea, where they are heated, chilled and shaken about before coming back to Kentucky to be bottled. Exact numbers of barrels aren’t available, but multiple shipping containers with 200 barrels each are now sent on these voyages. The 200-300 bottles that are filled from each barrel retail at $83 (about £60)2 for a 750 ml bottle, more than double their standard bourbon ($31).

Without good roads, the best option was for distillers to send barrels down the Mississippi with the spring flood, then by ship from New Orleans to New York for bottling. In 2022, Jefferson’s sent two barrels of bourbon on a replica journey down the Mississippi and then to New York to see if this process was the source of Kentucky bourbon’s high reputation.

The agitation of the spirit in the barrel during transit did change the flavour, both chemical analysis and blind tasting showed a distinct variation. This could explain the good reputation that Kentucky bourbon enjoyed in New York.

Relevance to whisky

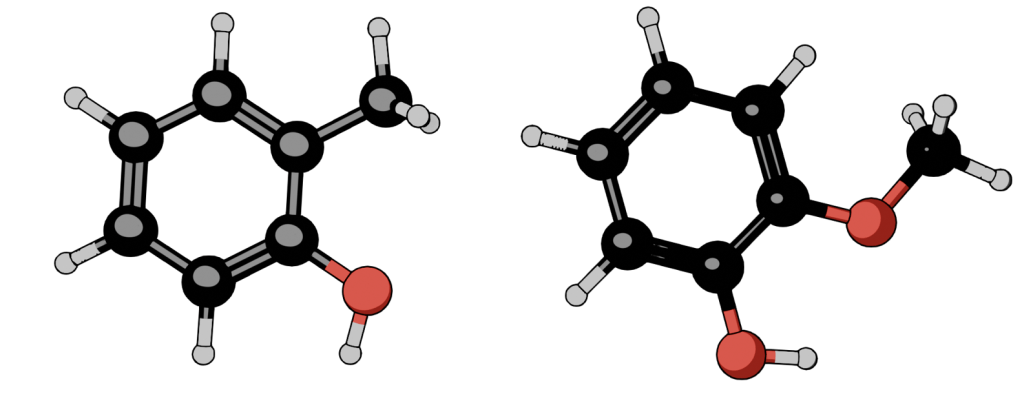

Bourbon is similar to whisky, in that you take a grain-derived spirit and age it in wooden barrels until it has absorbed flavours from the barrels and the environment. The difference is the type of grain you use. Malt whisky is made using barley. By law, bourbon must contain over 51% corn grain spirit. Anything else is grain whisky3.

As my previous blog discussed, a lot of whisky is aged in used bourbon barrels. The environment in which the whisky aging takes place influences the flavours extracted from the wood. Bourbon is produced in the generally temperate continental climate of Kentucky, so the mix of grains (the ‘mash bill’), the type of still used and the cut of the spirit are more important in determining the particular flavour4 of the bourbon.

The flavours extracted from used bourbon barrels by the maturing whisky will be representative of the original spirit. The mix of flavour molecules extracted will also vary depending on several factors including the ethanol content of the whisky, temperature, humidity, and time.

Scotland is a cool, damp country and produces characteristic whisky. By law whisky must be aged for at least three years to be sold as Scottish whisky. Age adds to the flavour, smoothness and cost of a whisky. The oldest whisky I’ve ever has is a 20 year old Highland Park – a slightly peaty but incredibly smooth drink that cost about £25 for a double5.

Japan and the getting back to the point

All this is fine, but what does the Jefferson bourbon experiment have to do with whisky? After all, shipping or moving thousands of heavy barrels isn’t a commercially viable option unless you’re going to add a premium to an already expensive product.

Japan has a well-established whisky manufacturing culture, with the first whisky distillery – Suntory – opening near Kyoto in 1923. Following a disagreement between the founders, a second distillery, Nikka, was opened near Sapporo on the north island of Hokkaido. This site was chosen because the climate was more like Scotland than the sub-tropical Kyoto.

Japan’s whisky industry was established after thoroughly researching the Scottish methods and equipment, even buying old stills from distilleries and, in places, a climate that mimics that of Scottish. From those beginning decades ago, Japanese distilleries have developed the craft to produce a distinct drink that has its own place in the world of whisky.

What is perhaps unique in Japan is that is a whisky-producing country that also sits on a tectonically active region, at the junction of at least three active geological faults. Low intensity tremors are frequent throughout the islands with major quakes occurring annually.

So, while shipping thousands of barrels by sea to enhance the extraction of flavours isn’t economically feasible, it could be that the character of Japanese whisky is changed through frequent shaking by earthquakes. It could be that, in their quest to create a Scottish whisky with a Japanese feel, the geology of their country has gifted the Japanese whisky industry an added influence that the distillers of other countries will find it difficult to emulate.

- Traditionally, whisky is from Scotland, whiskey isn’t. Though some Japanese distilleries use ‘whisky’. ↩︎

- I had to enter an address in the USA to get this price. I picked 1060 West Addison St, Chicago. ↩︎

- Quinoa can be used to make whisky, even though it’s not technically a grain. ↩︎

- Or flavor. ↩︎

- This was at a work event where I’d seen £200 bottles of wine being bought, so I didn’t feel guilty about this small extravagance. ↩︎